1920

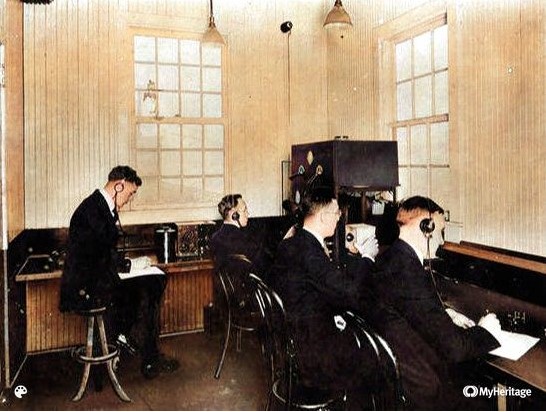

During the early months of 1920 the private Conrad laboratory had become a kind of beehive of radio activity, with enthusiasts and kindred spirits showing up for work and conversation every weekend.

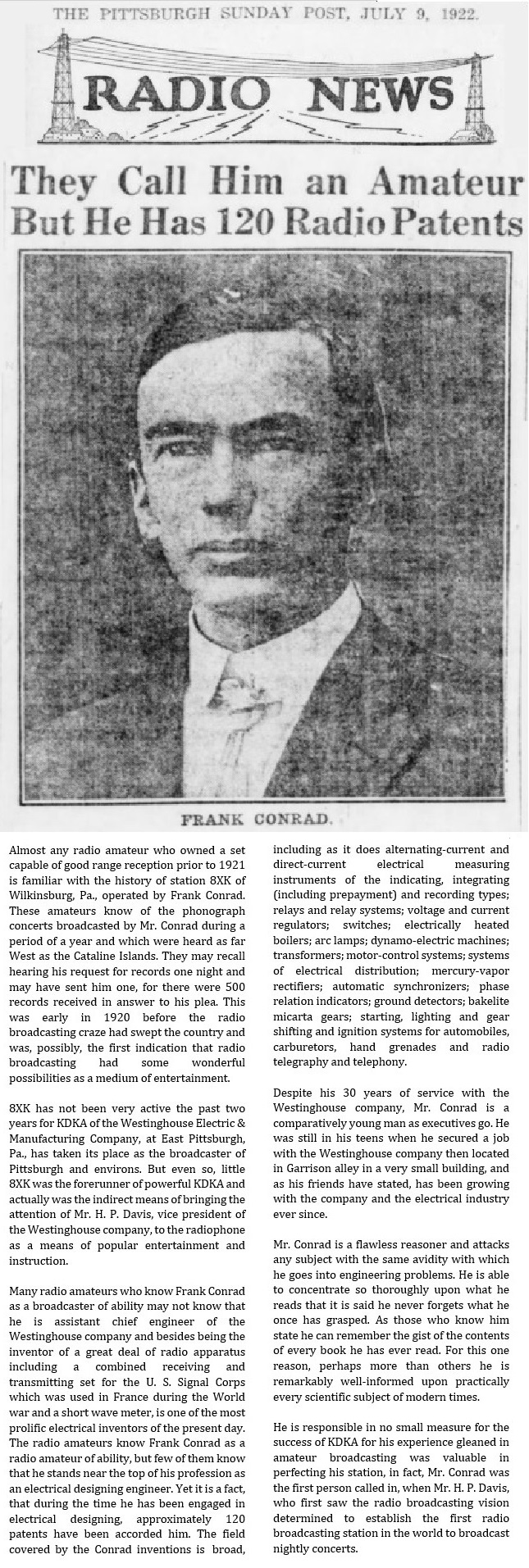

As time wore on, Conrad’s home station (call letters 8XK) more and more took on the appearance of a permanent radio station. Conrad’s two sons regularly worked as announcers; the Hamilton Music Store in Wilkinsburg loaned records, for which favor it was mentioned on the air. The music was well enough liked that eventually the Conrads started what seemed to be regular “concerts” on Saturday nights. Even the general public became aware of this burgeoning radio station, and Conrad garnered a certain amount of local notoriety.

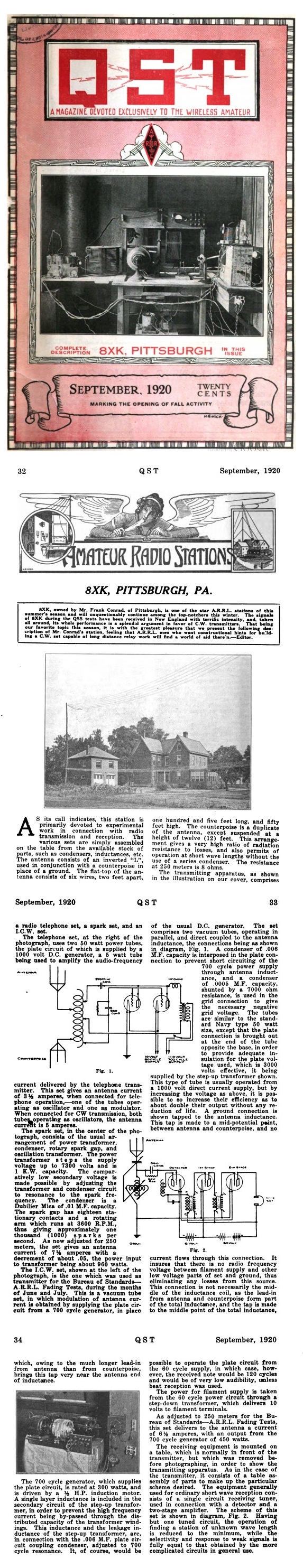

As the months of 1920 passed by, amateur interest increased. In September, Conrad’s station was a featured article in the amateur radio magazine QST and was featured on its cover. A number of people in the Pittsburgh area were wondering how they might be able to obtain sets of their own.

The Joseph Horne Department Store in Pittsburgh placed a newspaper ad notifying the public that the store had on display a radio set for amateur use that could pick up the Conrad radio programs. Not only was the Horne Company going to display and demonstrate this equipment, they were going to sell it as well: “Amateur Wireless Sets, made by the maker of the set which is in operation in our store, are on sale here, $10.00 up.”

Amateur wireless sets on sale! On sale to the general public, not just to the radio ham or bug! The day the ad appeared, Harry P. Davis, vice president at Westinghouse, saw the ad in the newspaper, and it aroused his interest. He was Conrad’s superior at Westinghouse, and of course he knew all about Conrad’s amateur broadcasts. But the sale of radio sets to the public – here was an idea that nobody had thought of before. Even if Westinghouse had been shoved out of the central core of the radio business as it now stood, perhaps something new could be drummed up. Sets not merely for radio “professionals” but for the general public—all made by Westinghouse, of course.

The day following the Horne advertisement, Davis held a conference with Conrad and other Westinghouse officials raising the possibility of building a bigger and more powerful transmitter at the Westinghouse plant, with the plan of offering radio broadcasting on a regular basis. In subsequent conferences Davis wondered if it would be possible to have a station and a suitable transmitter ready for regular operation in time for the Harding-Cox presidential election on November 2. Yes, it was definitely possible, said Conrad, and accordingly he and Donald Little were assigned to the task.

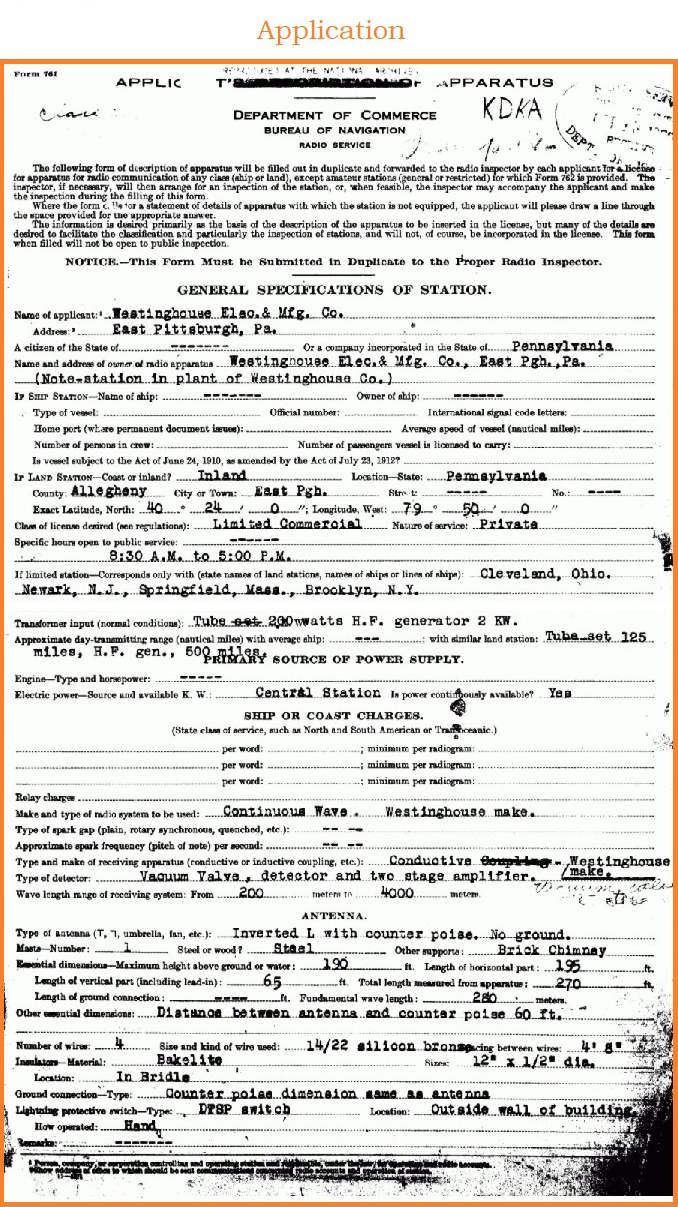

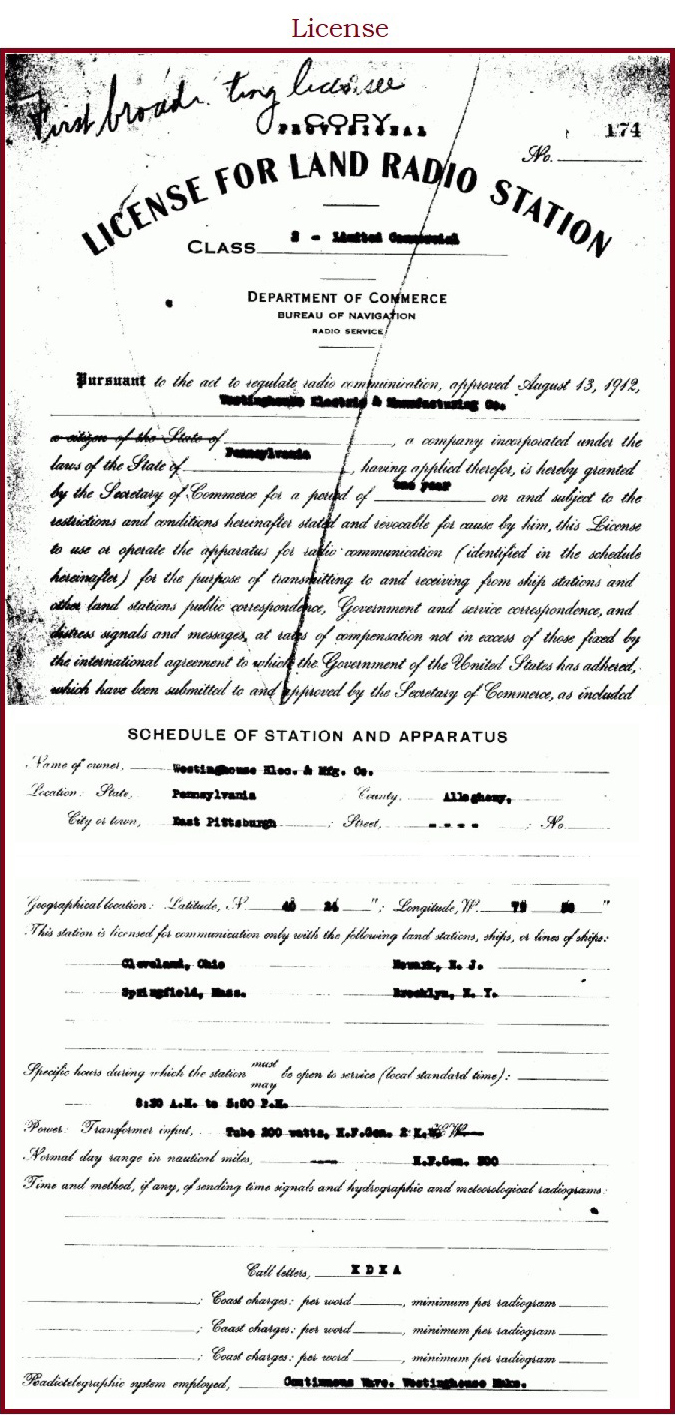

Prior to the emergence of the plan to broadcast election returns, Westinghouse had also been working on a point-to-point wireless communications system to be used among five of its industrial plants. Westinghouse applied to the United States Department of Commerce on October 16 for a “limited commercial” license for this purpose only, and on October 27, a license with call letters KDKA was issued. But this license did not address the broadcasting plan.

Recognizing that broadcasting with a commercial purpose was novel and without a licensing mechanism at the time, and after a telephone call with Westinghouse, the Commerce Department issued the amateur callsign 8ZZ for the broadcast.

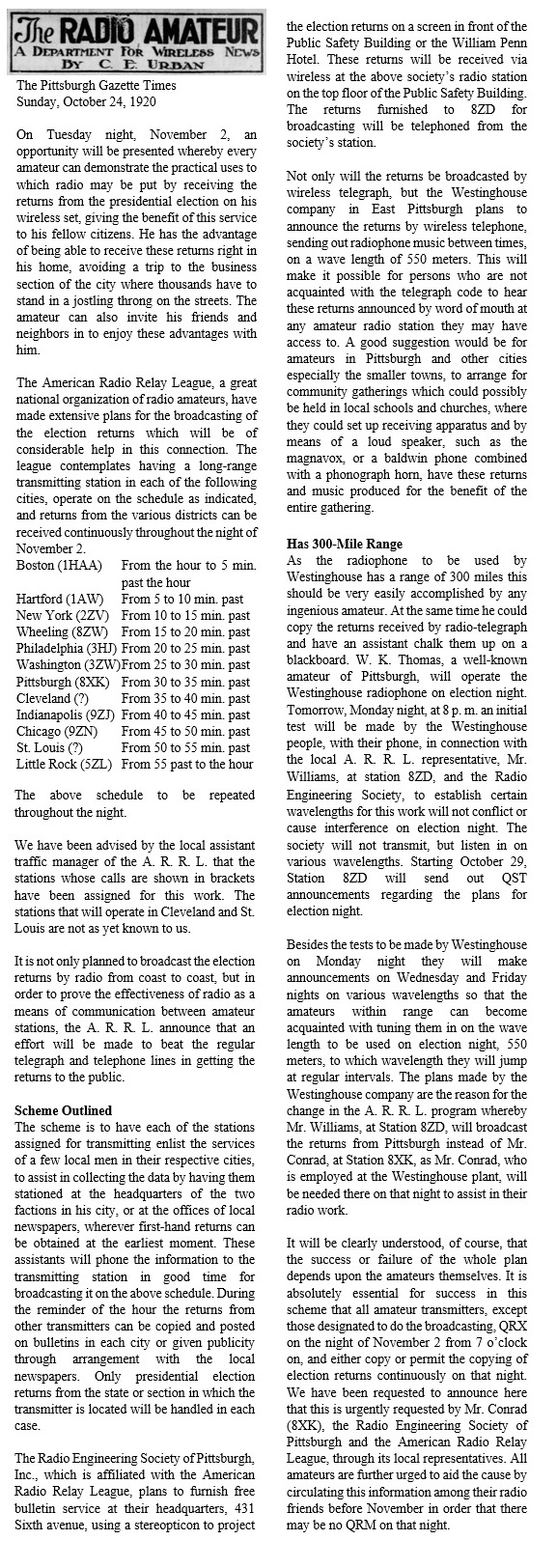

Westinghouse was also beginning production of sets for home use, and these, together with the imminent inauguration of programming, were given ample notice in the local press. A bi-weekly column, C. E. Urban’s “The Radio Amateur”, described the coming event in detail on Sunday, October 24, nine days before the election.

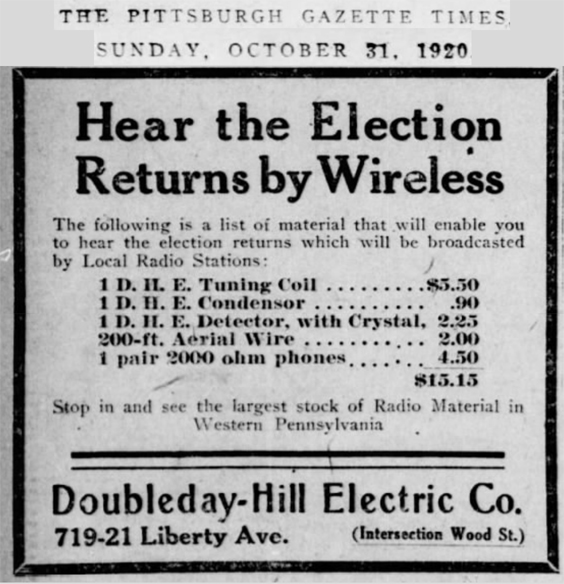

Arrangements were made to have the Pittsburgh Post telephone the election results to Westinghouse as soon as they became available from the news wire services. A newspaper ad on the Sunday before the election offered parts for $15 to enable reception of the election returns.

The big night came and went without a hitch. To be on the safe side Frank Conrad was standing by at his own 8XK transmitter in Wilkinsburg, prepared to send out the returns from there if necessary. But it wasn’t necessary, and the broadcast commenced at 8 PM. Most historical references indicate that the callsign of 8ZZ was used for that historic first broadcast.

The evening was a smashing success, and the next day scores of telephone calls from listeners came through the Westinghouse switchboard. There were many more listeners than there were sets, listeners mainly gathering in large numbers at central locations—churches, lodges, the private homes of Westinghouse executives—to be guinea pigs for the experiment. Everyone was delighted.

Historically, the important thing was that KDKA did not simply turn off its power and fold up after the election night special, but, as promised, continued its nightly broadcasts on a regular basis. At first the broadcast time was a single hour—8:30 to 9:30 P.M.—but before long the schedule would be expanded.

For the first time a radio station had attempted to appeal to a mass audience. KDKA’s intent was to sell sets to the general public—not sets by the dozen, but, as things turned out, by the millions. When the year 1920 began the only people who thought about radio thought of it as an art that could be understood and enjoyed only by the expert or the electronics whiz. When the year 1920 was over there were few who failed to see that radio was calling out to everybody. Now it just might be that the radio receiver could be a household utility like the stove, the phonograph and the electric light. The technology of home reception was still primitive, but the institution was there.